One evening last week in the heart of the City a bunch of bright minds gathered to find out about “Impact Investing: What you need to know in 90 minutes” at an event by Finance Matters at Escape the City. Escape the City and Finance Matters are new, fast-growing communities that inspire and connect young professionals who want to match their considerable talents to opportunities that deliver positive, social or environmental impacts. Escape the City itself helps young professionals broadly make a career change into entrepreneurial, adventure or impact-led opportunities., where as Finance Matters specialises in helping people in finance put sustainability at the heart of their career – whether that means through moving into a new role, re-designing their day job, or investing their time and capital for greater impact.

One evening last week in the heart of the City a bunch of bright minds gathered to find out about “Impact Investing: What you need to know in 90 minutes” at an event by Finance Matters at Escape the City. Escape the City and Finance Matters are new, fast-growing communities that inspire and connect young professionals who want to match their considerable talents to opportunities that deliver positive, social or environmental impacts. Escape the City itself helps young professionals broadly make a career change into entrepreneurial, adventure or impact-led opportunities., where as Finance Matters specialises in helping people in finance put sustainability at the heart of their career – whether that means through moving into a new role, re-designing their day job, or investing their time and capital for greater impact.

The recent report from the Social Impact Investment Taskforce, “Impact Investment: the Invisible Heart of the Markets” defines impact investments as, “those that intentionally target specific social objectives along with a financial return and measure the achievement of both”. While growing, impact investments are only a tiny fraction of the $210 trillion invested in global financial markets, and of the $100trillion (OECD estimate) global community of long-term asset owners (endowments, family offices, insurance companies, pension holders). However, impact investing is gathering momentum as the public and private sector recognise that addressing key societal challenges such as environmental, life (such as health and longevity), or socio-economic risks are too large and too complex to be tackled by cash-strapped governments alone. In 2013, several new institutional investors declared their interest in impact investments, as outlined in the J.P. Morgan/GIIN report: Spotlight on the Market: The Impact Investor Survey.

Bon-mots from the great and the good were pasted to the walls of the stairway up to the event urging attendees to take broader look at the meaning of success. The very embodiment of assertions that Millenials expect business to be responsible, and profitable, or perhaps the micro version of macro discussions about moving beyond GDP for better a measure of prosperity or progress.

Bon-mots from the great and the good were pasted to the walls of the stairway up to the event urging attendees to take broader look at the meaning of success. The very embodiment of assertions that Millenials expect business to be responsible, and profitable, or perhaps the micro version of macro discussions about moving beyond GDP for better a measure of prosperity or progress.

“Doing good and doing well are no longer seen as incompatible. There is a growing desire to reconnect work with meaning and purpose, to make a difference.” Social Impact Investment Taskforce

Brief introductions described a corps of finance professionals with some representation from business school graduates, existing impact investors and a couple from not-for-profits. Then the speaker, Dara Nikolova kicked off with an exercise asking small groups to decide which of five case studies to invest in. Several finance professionals immediately focused on the financial returns of the case studies. Yet the case studies presented investments in different sectors and geographies, reflecting the more complex and nuanced equation of risk, return and intended outcome of impact investing.

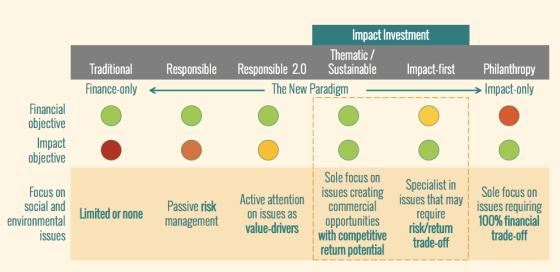

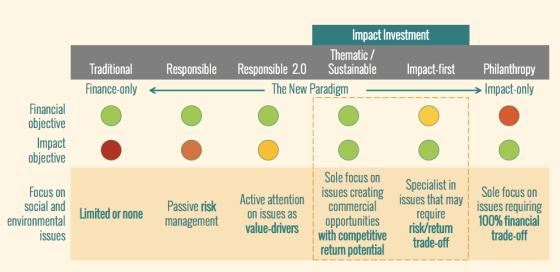

Intention (to have impact) is one of the key criteria that the Global Impact Investment Network uses to define impact investing. Impact investing also has to deliver a financial return on capital, and measurable impact – but it can be executed across a range of asset classes and with a range of return expectations.

The relative balance of these characteristics determines an invest’s location on the continuum shown right (courtesy of Finance Matters, adapted from Bridges Ventures). There is a spectrum of investment strategies that stretches from purely financial to pure philanthropy, defined by the investor’s relative emphasis on social & environmental factors, intention to have impact, and willingness to sacrifice financial returns relative to risk.

The relative balance of these characteristics determines an invest’s location on the continuum shown right (courtesy of Finance Matters, adapted from Bridges Ventures). There is a spectrum of investment strategies that stretches from purely financial to pure philanthropy, defined by the investor’s relative emphasis on social & environmental factors, intention to have impact, and willingness to sacrifice financial returns relative to risk.

Discussion on which would be the best investment of the case studies, was lively, if inconclusive, and a wonderful introduction to the complexity of impact investing. Dara went on to explore each of GIIN’s principal characteristics. Madeleine Evans, co-Founder of Finance Matters, then described how approaches to due diligence, investment structure, and portfolio management approach may differ for impact investors. One area of particular emphasis for impact investors is the link between revenue drivers and intended outcome in an proposed business model, that is to say whether the company’s target market, cost structure, and operating environment are likely to reward the enterprise for delivering on its intended impact. For The Gym Group, one of the case studies, some argued that target outcome and revenues are aligned, as the more members and gym correlates with greater EBITDA. Those less keen on the Gym Group’s candidature argued that although footfall would be growing is this an adequate measure of wider positive social impact? How do we know that users are not swapping from other facilities on the basis of price? Does it matter?

Measurement is at the heart of impact investing. Balanced Scorecard; Impact Return on Investment; Theory of Change and Logic Model represent some of the most widely recognised tools used by impact investors and social entrepreneurs to structure and track their activities and inputs in order to most efficiently deliver on their target outcomes. Lack of transparency and credible metrics has been a break on the growth of the impact investment industry. Currently, there are a range of impact accounting systems: Global Reporting Initiative, Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, GIIN’s Impact Reporting and Investment Standards and Global Impact Investing Ratings System, so we are some way away from being able to present standardised measurement of social impact alongside financial performance data. As well as asking what we can measure, there are questions of whether measurement skews priorities.

The impact investment landscape is complex, fast-changing and set to grow. It is an industry offering opportunities that more than match the ambition of the bright minds that want to Escape the City! Dara Nikolova’s talk set out some first steps for enlightened finance professionals to follow. The full slide deck is available on SlideShare.

There was a real buzz in the air afterwards as attendees talked animatedly about the content, before heading for a drink to ruminate further. A throughly stimulating evening in the heart of the City. If I have whet your appetite, both Escape the City & Finance Matters have a series of interesting events coming up, and on Wednesday 22nd October, Finance Hub from Guardian Sustainable Business will be hosting a live chat, “How to invest in social and environmental change”.

P.S. The Eden Project, the award-winning visitor attraction with internationally recognised biomes. has just broken the record for the quickest Crowdcube Mini-Bond, raising a total of £1.5 million in less than 24 hours from 355 people to develop a new space for its educational programme and give young people their first taste of horticulture. There is certainly an appetite for impact investment!

The first talk of the SustainRCA 2014/15 year, Joining the Dots, drew quite a crowd. Held in collaboration with the People’s Parliament the event was held in a House of Commons committee room. A fitting location as transparency, accountability and human rights are at the heart of the push to join the dots on the supply chain. Baroness Lola Young introduced the speakers, and the evening, in the context of the Modern Slavery Bill. The Bill, due for its second reading in the House of Lords on 17th November 2014, will compel large companies to annually disclose what they have done to ensure their supply chains are “slavery free”. As well as regulatory pressure, customers increasingly expect businesses to delivery great products and services responsibly. The demand for greater transparency is matched with growing interest in the narrative behind products, a desire for authenticity, the result of a centrifugal force driving remote, homogenous, global brands at one extreme, and a revival of artisan, heritage and craft at the other.

The first talk of the SustainRCA 2014/15 year, Joining the Dots, drew quite a crowd. Held in collaboration with the People’s Parliament the event was held in a House of Commons committee room. A fitting location as transparency, accountability and human rights are at the heart of the push to join the dots on the supply chain. Baroness Lola Young introduced the speakers, and the evening, in the context of the Modern Slavery Bill. The Bill, due for its second reading in the House of Lords on 17th November 2014, will compel large companies to annually disclose what they have done to ensure their supply chains are “slavery free”. As well as regulatory pressure, customers increasingly expect businesses to delivery great products and services responsibly. The demand for greater transparency is matched with growing interest in the narrative behind products, a desire for authenticity, the result of a centrifugal force driving remote, homogenous, global brands at one extreme, and a revival of artisan, heritage and craft at the other. Celebrating materials, maker and method gives meaning to a product, in fact the object derives greater meaning from the sum of these stories, and here lies the rationale for Provenance, a new online retail proposition from RCA graduate Jess Baker. Every product has a story in its supply chain, and “not all products are created equal”. Baker felt that retail experiences where look and price are the only metrics available are missing something and she suggested customers would pay up to 70% more if they knew that the benefits were going to the local community. Observation made, Baker, with a PhD in computer science, is optimistic that technology can help us be better citizens, redressing the informational asymmetry that currently defines the retail experience. Provenance tells the story of the people, places, processes and materials behind products. Oh joy to discover I live a stone’s throw away from where Prestat, chocolate purveyor to H.M. The Queen is making dark salted caramel truffles! The Provenance API offers makers a host of smart perks, such as the ability to serve stories on other sites, but essentially it is the products’ stories that provide the marketing clout.

Celebrating materials, maker and method gives meaning to a product, in fact the object derives greater meaning from the sum of these stories, and here lies the rationale for Provenance, a new online retail proposition from RCA graduate Jess Baker. Every product has a story in its supply chain, and “not all products are created equal”. Baker felt that retail experiences where look and price are the only metrics available are missing something and she suggested customers would pay up to 70% more if they knew that the benefits were going to the local community. Observation made, Baker, with a PhD in computer science, is optimistic that technology can help us be better citizens, redressing the informational asymmetry that currently defines the retail experience. Provenance tells the story of the people, places, processes and materials behind products. Oh joy to discover I live a stone’s throw away from where Prestat, chocolate purveyor to H.M. The Queen is making dark salted caramel truffles! The Provenance API offers makers a host of smart perks, such as the ability to serve stories on other sites, but essentially it is the products’ stories that provide the marketing clout. The final speaker, Bruno Pieters, designer and founder of Honest by, is striving to be the first company in the world to offer customers price transparency. Pieters is an entrepreneur, fashion designer and art director well-known for his sharp tailoring developed while working with designers such as Martin Margiela, Thimister and Christian Lacroix. Pieters returned from a sabbatical in India, with a deep-seated concern for the environment, and wider impact of fashion industry. His vision brings radical transparency to the entire supply chain. Click on an item that catches your eye and, in addition, to conventional information about the garment’s size and care, scroll down for details of the material, manufacture, carbon footprint, and price calculation: with 0.5 euros of thread, and the retail mark-up. What a fascinating exercise!

The final speaker, Bruno Pieters, designer and founder of Honest by, is striving to be the first company in the world to offer customers price transparency. Pieters is an entrepreneur, fashion designer and art director well-known for his sharp tailoring developed while working with designers such as Martin Margiela, Thimister and Christian Lacroix. Pieters returned from a sabbatical in India, with a deep-seated concern for the environment, and wider impact of fashion industry. His vision brings radical transparency to the entire supply chain. Click on an item that catches your eye and, in addition, to conventional information about the garment’s size and care, scroll down for details of the material, manufacture, carbon footprint, and price calculation: with 0.5 euros of thread, and the retail mark-up. What a fascinating exercise!

ic, materials and equipment. Oomph’s theory of change is based on exercise improving physical and mental health, reducing accident rates, and enabling care homes to provide a better quality of service addressed NIM’s ageing outcome. Oomph and NIM worked together to develop an impact evaluation plan around targets to develop evidence proving a correlation between Oomph’s growth and the target outcome. This is typical of NIM’s involvement, coupled with board support.

ic, materials and equipment. Oomph’s theory of change is based on exercise improving physical and mental health, reducing accident rates, and enabling care homes to provide a better quality of service addressed NIM’s ageing outcome. Oomph and NIM worked together to develop an impact evaluation plan around targets to develop evidence proving a correlation between Oomph’s growth and the target outcome. This is typical of NIM’s involvement, coupled with board support.